Te Aro Wine was established in early 2018 with a mission of creating “fun wine, not fine wine” by Robin Groves and Jules van Costello. But have they succeeded?

“The reception has been overwhelmingly positive,” Groves said. “We’ve been really pleased with it.”

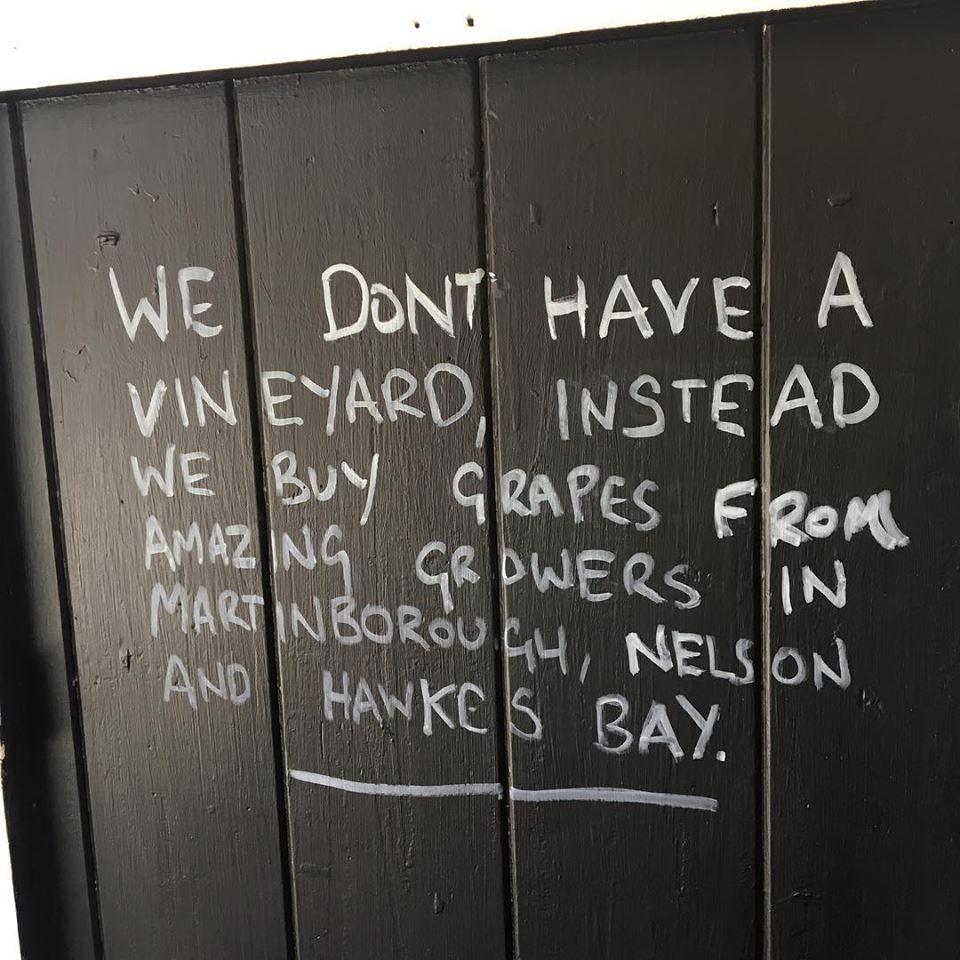

The definition of an urban winery is a simple one – a winemaking facility in an urban setting, away from the traditional rural setting of a vineyard.

“It’s a pretty big movement internationally,” van Costello said. “Obviously there are plenty in cities in wine regions, but now we’re seeing them in places which aren’t known for wine, like Sweden.”

The ‘urban winery’ movement is slowing gaining pace. Te Aro Wine isn’t the first in New Zealand (there are urban wineries in Dunedin and Hawkes Bay, and Garage Project has experimented with wine in the last year as well), and there are urban wineries in cities like London and Gothenburg – hardly known as wine-producing centres. Based across the road from the old Ford factory in inner-city Wellington, Te Aro Wine is about as urban as it can get.

Wellington has been saturated with craft beer breweries in recent years, and the pair wanted to do the same with wine.

“Wellington needed something fresh,” van Costello explained. “We jumped on the bandwagon on craft breweries opening cellar doors and did it with wine.”

“Why? Because we can,” Groves added.

While neither Groves nor van Costello has completed any formal winemaking training, both are keen wine lovers. Groves worked as a chef on the fine dining circuit in his early career before moving into business, and van Costello runs the online wine store Cult Wine. When it comes to vintage time, the pair share the winemaking duties – enrolling the aid of friends, family, and members of the hospitality community.

While Te Aro wines aren’t strictly natural – although Groves and van Costello hope to source from certified organic suppliers, organic certification in itself is a rigorous process – the pair believe in letting the wine speak for itself and try to keep out of the process as much as possible. Under the traditional winemaking model, big wine companies tend to interfere with the process to create a product consistent with the brand and customer expectations.

“We don’t want to do that at all, Groves said. “We make fun wine, not fine wine.”

“We want wine to be a bit more fun for people,” van Costello added. “Wine has got a relatively stiff reputation, so we want to present in a way relaxed, engaging way that’s a bit more accessible.”

Does this mean that they think that the New Zealand wine industry takes itself too seriously? Not at all.

“On a global scale, the industry needs to take itself seriously,” Groves said. “That’s the New Zealand brand – a boutique option compared to the mass wine industry in Australia, so that’s how it’s perceived overseas. In New Zealand itself, though, there is room for improvement. Young people are drinking craft beer and gin because that’s what’s cool – it isn’t your mum or dad’s drink.”

The lack of expectation in regards to taste with an urban winery is an advantage.

“When people drink a Martinborough wine, they expect it to taste like a Martinborough wine,” Groves said. “We don’t have that, so really we can do what we want.”

“We’re quite happy to operate in our own space,” van Costello said.

Running an urban winery comes with its own set of challenges. When the pair approached Wellington City Council in order to get their plans approved, the Council didn’t quite know what to do.

“In a wine-producing area the local Council knows exactly what to do and how to get it done,” Groves said. “Not so much in central Wellington.”

Luckily they had a tolerant landlord, who also worked in hospitality and helped them get off the ground. It also came in handy during vintage – the upstairs neighbours were not as tolerant of the fermentation smells rising from below.

Running a small-scale operation, especially one as experimental as Te Aro Wine, means that the pair can take risks with a lessened level of financial hardship. An example of this is BeesBeesBees, where the pair used flora honey for secondary fermentation, transforming a still wine into sparkling wine.

However, naming the ‘wine’ was going to be a problem as honey is not a permitted wine additive.

“To be honest, we can’t even call it wine,” said van Costello, “so we call it what it is: skin-fermented Martinborough Sauvignon Blanc re-fermented with honey.”

“If we try something and it doesn’t work out then we can move on,” Groves explained. “Obviously there will be some financial losses down the line, but it won’t be an immediate loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

“Even if it doesn’t work out,” quipped van Costello, “we can always just start selling vinegar.”